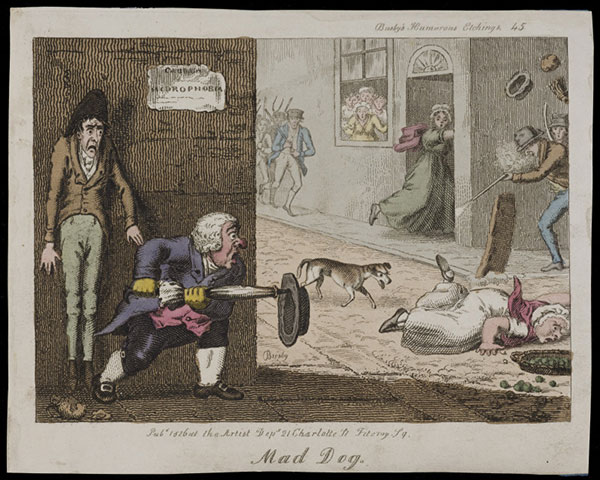

Rabies is a scourge as old as human civilization, and the terror of its manifestation is a fundamental human fear, because it challenges the boundary of humanity itself. That is, it troubles the line where man ends and animal begins—for the rabid bite is the visible symbol of the animal infecting the human, of an illness in a creature metamorphosing demonstrably into that same illness in a person.

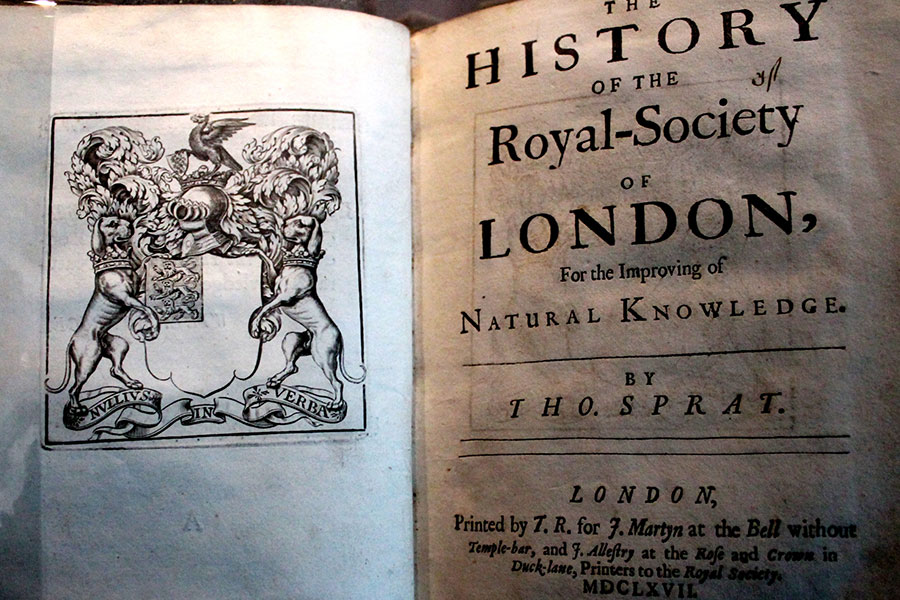

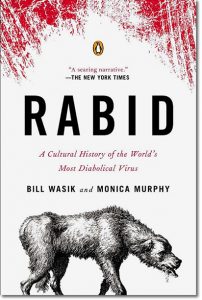

— Rabid: A Cultural History of the World’s Most Diabolical Virus

By Bill Wasik and Monica Murphy

With the release of our line of 2020 Pet Rabies Tags for our customers’ dogs and cats, we at Ketchum Mfg. Inc. thought this would be an appropriate time to present a timeline of notable events in the rise of—and ongoing battle against—a pathogen that has plagued humankind and our domesticated animals since long before the first history book was written: the rabies virus.

4 Billion Years Ago

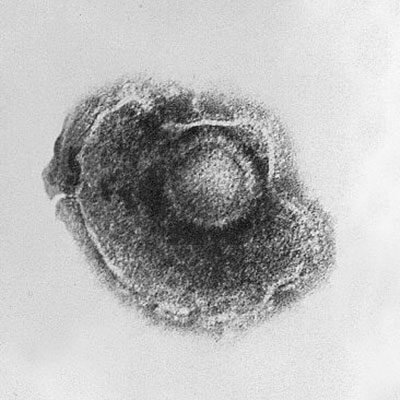

Viruses are significantly different from other lifeforms. Virologists can’t even agree on whether to characterize them as “life” per se, since these infectious agents do not breathe oxygen, have no need to ingest and metabolize nutrients, lack a cell structure, and are unable to reproduce without a host organism. All they can do is self-replicate using a host cell’s genes and (being subject to laws of natural selection) mutate into different strains of itself.

What is indisputable is that viruses are ancient and are the most abundant biological entities on the planet, outnumbering all others put together by far. They are found wherever there is cellular life, and they have no doubt existed at least since living cells first evolved. And they are equal-opportunity pathogens: viruses are known to infect all types of cellular life, including animals of land, sea and air, insects, plants, bacteria, and even fungi.

160 Million Years Ago

Cross-species transmission, or “spillover,” is the ability of a foreign virus, once introduced into an individual of a new host species, to adapt its genetic code to an unfamiliar environment, infect that individual, and spread throughout a new host population. Thus, at some point in time a bacterial, plant, insect, or saurian viral agent must have species-hopped into some early proto-mammalian creature like Juramaia, overcame the animal’s host-specific immunological defenses, and then became pathogenic. The rest, as they say, is history.

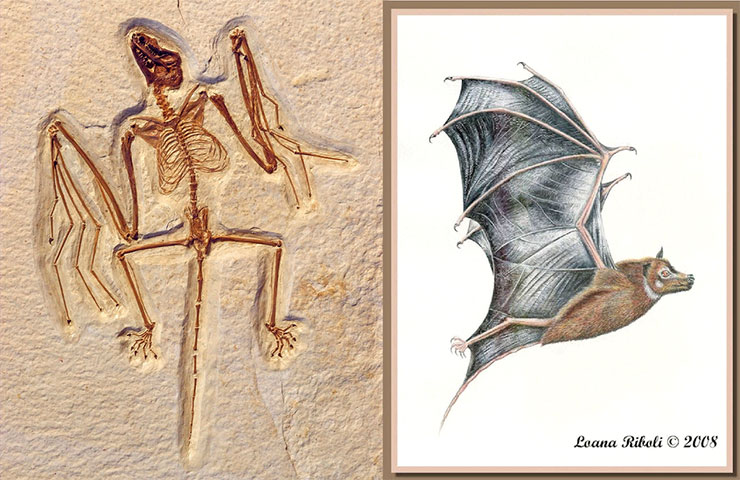

55 Million Years Ago

The Eocene period marks the first known appearance in the fossil record of mammals of the order Chiroptera—that is to say, bats. It is not known whether the distant ancestors of today’s flying, largely nocturnal creatures were susceptible to the rabies virus, or whether that virus even existed at the time. Nevertheless, in the modern era, bats account for the majority of wild animal cases of rabies infection (about 30%) reported in the United States.

The rabies virus has an exceptionally broad host-range: all warm-blooded mammals, including humans, may become infected with the rabies virus and later develop symptoms. It is usually present in the nerve tissue and saliva of a symptomatic animal, which is why the bite from a rabid animal is so dangerous. Besides infected bats, the animals that present the greatest risk to humans include raccoons, foxes, skunks, wolves, coyotes, dogs, cats, ferrets, and mongooses. Globally, dogs account for the majority of rabies cases in humans caused by an animal bite.

Mammals have little or no natural immunological defense against rabies infection (in a previous article we have discussed the risks and symptoms of rabies). Left untreated, rabies is virtually always fatal once neurological symptoms have developed in a person.

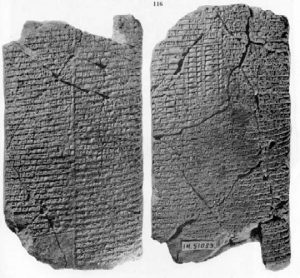

2000 B.C.

The first mention of rabies in the written record appears in the Law Code of Eshnunna, found on a set of cuneiform tablets from ancient Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq). Much like the Code of Hammurabi, this codex lays out “the rules of the road” for Akkadian citizens of antiquity, including penalties for violations of the laws.

One of those rules dictates that the owner of a dog showing symptoms of rabies must take preventive measure to protect others from bites. However, the law adds, if another person gets bitten by a rabid dog and later dies, the owner will be severely fined.

Even back then, clearly, rabies was recognized as a separate, particularly infectious, and invariably fatal disease. Later on, in his Historia Animalium, Aristotle writes that “Dogs are susceptible to three diseases: rabies, distemper, and hard-pad. Rabies makes the animal mad…. It is fatal to the dog itself, and to any animal it bites.”

79 A.D.

As for other cures, the medical writings of the ancient Greek, Roman, Islamic, and Medieval worlds are rife with folk remedies, all magical in nature. As such authors lacked a scientific understanding of the true cause of rabies, of course, none of these remedies worked.

Interestingly, Roman writers often used the Latin word virus (meaning “poison”) in referring to rabies infection. If only they knew how close they were to the truth!

The centuries leading up to the Middle Ages and following were marked by severe epizootics in wolves and foxes throughout Europe; and, with increasing urbanization, a natural “spillover” occurred affecting the canine populations in cities. The disease in wolves was especially feared, due to their ferocity and tendency to roam over large areas, spreading the disease and resulting in numerous human victims.

1796

The English physician Edward Jenner, “the father of immunology,” pioneers the world’s first vaccine. At the time, nothing was known about antibodies and antigens. Noting, however, that milkmaids (who were routinely exposed to cowpox, a disease similar to smallpox but much less virulent) were subsequently immune to the deadlier disease, Jenner theorized that something in the pus of the blisters that milkmaids received from cowpox protected them from smallpox, and so could protect others as well. Thus was born the most successful vaccine in history—for now smallpox is literally extinct in the wild worldwide. His work saved millions of lives and laid the groundwork for future immunological research.

1885

With the assistance of his colleague, Émile Roux, Pasteur produced the first vaccine for rabies by growing the virus in rabbits, harvesting it, and then weakening it by drying the animals’ affected nerve tissue.

After testing it successfully on 50 dogs, he finally tried the vaccine on a human patient (a 9-year-old boy mauled by a rabid dog). Pasteur was hailed as a hero, and the treatment’s success laid the foundation for the development of numerous other future vaccines.

1892–1898

In a scientific milestone, Dmitry Ivanovsky isolates a filtered, infectious, non-bacterial pathogen from a diseased tobacco plant. Recognizing that tobacco mosaic disease is a brand new, heretofore undiscovered lifeform, Martinus Beijerinck calls this pathogenic substance a “virus.” Thus begins the science of virology.

The invention of the electron microscope in 1931 allows the complex structures of viruses finally to be visualized.

1949

For the first time, a method is invented to grow viruses in cell cultures rather than in live animals. Jonas Salk uses this method to develop his polio vaccine in 1952. Growing viruses in cell cultures introduces a new paradigm, allowing the preparation of purified viruses for the mass-manufacture of safer, more effective anti-rabies vaccines for both humans and their pets.

1967

The rabies human diploid cell vaccine is developed, and is now commonly used to protect people who have been bitten by animals (post-exposure) or who otherwise may be exposed to the rabies virus (pre-exposure). Like Pasteur’s original vaccine, this treatment works by exposing the patient to a small dose of inactivated virus, which causes the body to quickly develop immunity to the disease before it can attack the nervous system and brain.

1979

The Van Houweling Research Laboratory of the Silliman University Medical Center in the Philippines develops and produces a dog vaccine that gives a three-year immunity from rabies. The successful use of the vaccine results in the elimination of rabies in parts of the Philippines and is later used as a model by other countries around the world.

2007

World Rabies Day (September 28) is first celebrated as an annual global health observance to raise awareness about rabies and bring together partners to enhance prevention and control efforts worldwide. World Rabies Day is observed in many countries, including the United States.

2019

Ketchum Mfg. Co. releases their heart-shaped 2020 Rabies Tags. For a limited time, get 20% off on your order!

2020 Rabies Tags

2020 Rabies Tags

2020 Rabies Tags

As this video shows, whether you are a vaccinator in a country where dog rabies is still a problem or a pet owner here in the U.S., we all have a crucial role to play in preventing the spread of this deadly disease and wiping it out entirely one day. Vaccinate your dogs and cats!